44

37

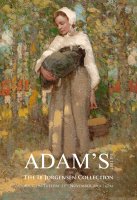

George Campbell RHA RUA (1917-1979)

Fishing Harbour, Night

Oil on board, 41 x 53cm (16.1 x 20.8”)

Signed, inscribed with title verso

Provenance: with Ritchie Hendriks Gallery, Dublin

‘It’s not possible to talk about art’, said George Campbell in a 1979 B.B.C. North-

ern Ireland interview. Words, he felt, were redundant when it came to painting. Al-

though regarded as a great raconteur, he rarely talked about his art. He was not given

to in-depth analysis of his work. Painting, for him, was a given; he did not choose

to paint, he was the paint’s medium. It was a process of sublimation whereby all his

day-to-day experiences would be stockpiled and then released in a cathartic burst of

creativity. ‘Open the door and let the wind carry it’, as he said to camera. He likened

himself to a sponge, constantly soaking up influences and images and storing them

up for future compositions as he almost invariably painted from memory.

In his earlier work he uses the line as language. In his hands it is a graceful, indeed

sensual, form of communication. He speaks of line the way an author would speak of

his characters: ‘incised lines, rough lines, nervous lines, architectural lines, depending

on what I expect them to do for me’. He developed beyond this to express himself

through colour and form. Very much an autodidact, a practiser of his own techniques

and theories, he was influenced by Cubism, at least at a pictorial level. He was not so

much influenced by the thinking of, say, Picasso and Braque as by the fruits of their

thinking. Late in life he quoted “Braque’s art is there to extend your approach, not to

make you feel comfortable and smug”.

The faceted planes and interlocking shapes of

Fishing Harbour, Night

, represent a

direct nod to Cubism.The Russian sculptor, Ossip Zadkine, encouraged George to-

wards abstraction by stressing the musical and spiritual qualities of paint. ‘I like your

controlled complexities’, he said. George absorbed this and reproduced it twenty-five

years later in his gun-metal grey/blue Irish seas. Nothing was ever lost with George;

everything went into his ‘ rusty archive’. George was proud of having formulated his

own disciplines and techniques. He enjoyed the fact that his work was scattered and

that the critics commented on the fact that his shows looked like group exhibitions.

‘Group exhibition on two legs!’, he proudly declares in the 1979 interview. He re-

joices in the fact that everything impinges on him. He boasts of his friend, James

McAuley, saying : ‘You’re such a bloody Celt. You cannot leave anything alone. You

want to go on to the edge.’ He admits to ‘painting diarrhoea’ and a craving for more

textures and more images. ‘I need my head hoovered out’, he said just weeks before

his death; he was teeming with ideas. In this programme he declares his intention to

do even more abstract paintings. George revelled in his own set of symbols and vo-

cabulary. He felt that in terms of painting words have no meaning and he described

the world of art criticism as a ‘big garden full of weeds and I’m looking for a daffodil’.

In a 1974 interview in Art About Ireland he made his feelings very clear : ‘I feel that

the aura of Inner Sanctum and intellectualism in Art should be broken down – it’s

visual – and that’s that’.

€4,000 - 6,000