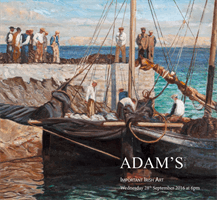

28

20 MARGARET CLARKE RHA (1888-1961)Portrait of the Artist Dermod O’Brien PRHA in his Studio

Oil on canvas, 125 x 100cm (49¼ x 39¼’’)

Signed and dated 1934

The frame has a plaque inscribed ‘Presented to Dermod O’Brien PRHA by a number of Friends and Admirers, 13 December 1934’. The artist’s daughter,

Brigid Ganly notes that the portrait on the easel is that of

Edward Bannon

of Broughal Castle, Offaly but also of New York, Newport and Florida; which she

thinks is one of the best portraits her father ever painted. It was presented by Mrs Banon to The National Gallery of Ireland.

Literature: “Palette and Plough” by Lennox Robinson 1948 - this picture used as frontispiece.

Margaret Clarke (1884-1961) was commissioned to paint this portrait of Dermod O’Brien by his many friends and admirers, who presented it to him as a

gift in 1934. O’Brien was a prominent figure in Irish life in the early part of the twentieth century, involved in many organisations, and a fervent supporter

of Horace Plunkett’s co-operative movement. His most enduring role was as President of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) from 1910 until his death in

1945. He was born in 1865 into a wealthy landowning family in Limerick that traced their ancestry back to Brian Boru. Though a Protestant and married to a

Unionist, he was politically unaligned, committed to helping Irish society develop socially and culturally. He said of himself that his driving force was ‘the thing

to be accomplished. It does not matter to me whether Ireland is saved by the priests, peoples, Orangemen or English...’

Margaret Clarke and Dermod O’Brien had known each other for many years. When Clarke’s husband, Harry Clarke, died in 1931, O’Brien offered Clarke not

only sympathy but assistance, should she need it. They had much in common. Clarke had been elected a full member of the RHA in 1928 - only the second

woman to be so honoured. They had both been thoroughly schooled in the traditional, academic approach to art - O’Brien in Antwerp, Clarke in Dublin under

Orpen - but they were generous, active supporters of less traditional, more radical artists, and sat together on committees such as the Irish Exhibition of

Living Art. When O’Brien learnt that Clarke was to paint him, he wrote to her to say how very pleased he was. Elsewhere, he praised the sincerity, insight and

characterization of her portraiture, and her ability ‘to search into the character of the sitter and get at the soul of him or her’.

However, always the organiser, O’Brien began to issue instructions: he did not want to be shown as an important official in robes and chains, but neither did

he want her to portray him as a plain citizen. Half-jokingly, he told her to make him ‘beautiful and sympathetic and dignified, and at the same time humble

and diffident’. Clarke painted him in his role of artist, paintbrush in hand, standing in front of his easel, but not looking at it. He is formally dressed, bristling

with the air of a man of authority poised for action, seeking the next challenge. At Clarke’s suggestion, perhaps to balance his obvious dignity with the re-

quested humility, he donned a crios, the belt worn by peasants of the Aran Islands. According to his daughter, Brigid Ganly, herself an artist, this is the best

portrait ever painted of O’Brien: ‘absolutely characteristic in the pose of the head, the alert glance, the quick humour of the mouth’.

O’Brien remained a lifelong advocate of Clarke’s work, helping her to get commissions and advising bodies such as the Haverty Trust to purchase her

paintings.

Fiana Griffin September 2016

€ 8,000 - 12,000