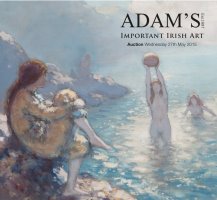

25

Norah McGuinness HRHA (1901 - 1980)

Perugia

25

Norah McGuinness HRHA (1901 - 1980)

Perugia

Oil on board, 56 x 76 cm (22 x 30”)

Signed

Exhibited: Biennale Internazionale d’Arte di Venezia, Venice 1950, Catalogue No.64.

:Norah McGuinness Exhibition:, The Leicester Galleries, London, June 1951, Catalogue No.13.

In 1948, the Venice Biennale resumed after the Second World War, the twenty-fourth Biennale in 53 years. However it was the

following Biennale, of 1950, that would be significant in an Irish cultural and art historical context. In Room 50 of the central Italian

Pavilion, Ireland was represented for the first time in the Biennale’s history. What is most fascinating about this Irish Pavilion is that

as a country newly emerged from the Commonwealth, one which had been presented with a moment of opportunity to define the

national, cultural and political identity of its newly independent state; Ireland chose to be represented exclusively by women artists.

In a delegation of 850 artists from 24 countries, Ireland was unique in this aspect, although other countries did include women

amongst their delegations.

The two Irish women who were chosen to represent the country had of course, already been hugely instrumental in the develop-

ment of modernism in Ireland. Norah McGuinness and Nano Reid, contemporaries in age, artistic training and back ground (neither

had the privilege or financial backing of an Anglo-Irish family as artists such as Hone and Jellett did); they had each significantly

influenced the evolution of the modernist landscape in Ireland, in spite of differences in their artistic styles.

Each artist submitted twelve works, McGuinness including only works which, according to Fiona Barber’s account of the Bien-

nale, “Excavating Room 50”, were completed in 1950. McGuinness had by this time, returned to Ireland as War plagued mainland

Europe. Previously she had spent a period living in New York after her marriage to poet Geoffrey Phibs ended in 1931. Here she

supported herself as a window dresser out of her Greenwich Village studio. As a woman living at a time when women’s roles within

society were increasingly domestic, she was almost unique in her entrepreneurial abilities and independence. After returning to

Ireland at the onset of the War, McGuinness became involved in the instigation of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA), the first

significant recognised alternative to the power of the more traditional and conservative Royal Hibernian Academy. After the death

of artist Mainie Jellett in 1944, McGuinness took over the chair of the IELA, holding the role for almost twenty years. Her city life is

reflected in the subject matter of her work which during this period was dominated by urban scenes. Of her twelve works included

in the Biennale, at least two include scenes of the River Liffey running through Dublin’s industrialised city centre, while others, such

as Promenade and Perugia, hint at a more European city landscape. The softer tones of the palettes used in these works suggest

a warmer climate. McGuinness’s engagement with the bright jewel-like colours in Perugia entice the eye; and yet, the dark outlines

of the figures on the balcony suggest something sinister is at play. The dark figure lurking to the left of the foreground overlooking

the town threatens the sunny scene below; yet this is contradicted by the pleasant naivety and innocence of both the pair who

converse in the opposite corner of the foreground and the presence of the child to the centre. One could draw many parallels from

the body language of these characters with McGuinness’s own personal life and experiences as an independent divorcee.

What is intriguing about Ireland’s participation in the 1950 Biennale is that there is almost no record of the event. Although one

might imagine the event to have been hugely significant both in terms of the development of Irish modernism in the international

spectrum and as a highlight in the careers of both artists, there is little or no mention of it either in surveys of Irish art or in govern-

ment records from the period. The disappearance of this special moment in Irish art history from the annals of Irish modernism and

visual art in Ireland may be explained by the fact that none of the 24 works shown in Venice are in public collections. Perugia is one

of only twelve pictures by McGuinness bearing this unique mark of history, and as such, it is an especially important piece of both

McGuinness’s and Ireland’s artistic history.

Katie McGale May 2015

€8,000 - €12,000