IRISH FURNITURE - AUCTIONS AND ACQUISITIONS, ANGELA ALEXANDER

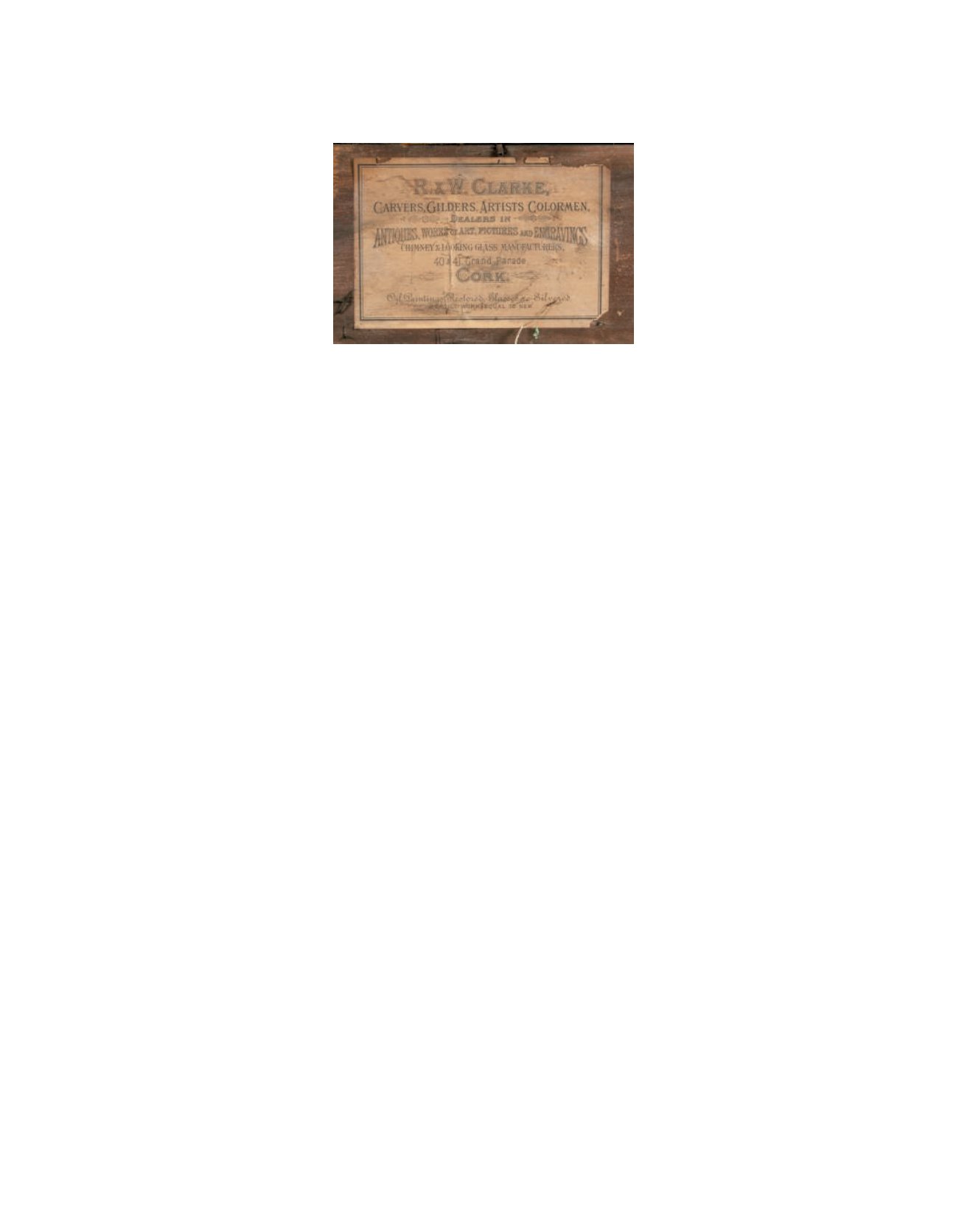

The interest in Irish furniture has grown in recent years with a particular appreciation of pieces with provenance and those that are labelled

and stamped. Auctions have long been a favoured process for buying art and objects. In Ireland in the early nineteenth century buying

at auction became increasingly popular as a greater selection of goods became available. During this period Dublin remained the centre

of business and social activity with building resuming after the Act of Union was passed, as rents from land increased and confidence

returned. Houses were bought and sold, contents auctioned and many newly furnished. The second and third sons of many ascendancy

families established careers in commerce and in particular, in the early nineteenth century, turned to the law, in addition to the more tra-

ditional roles they had always followed in the army and the church. Sir Jonah Barrington famously divided gentlemen into three categories:

half-mounted gents, every-inch gents and gents-to-the-backbone.(i) Society remained mobile, which added vibrancy and, as stated, result-

ed in property changing hands more frequently. As Sir Vere Hunt remarked when he attended the auction of the belongings of a Mr Isaac

who, having furnished his house in a most magnificent style, found out his error and miscalculation as to his means to support it; ‘and all, of

course went to the hammer – Going! Going! Just going! Gone!!! (ii)

Furniture with provenance allows us a glimpse into its particular history and an insight into the house it came from. This is the case with

an eighteenth century Chinese Chippendale style mirror (Lot 82), part of the original contents of Kilsharvan House, County Meath. Andrew

Armstrong moved from Antrim, buying the original eighteenth century house at Kilsharvan and continued his linen business on his land in

County Meath. He may have purchased some of the earlier pieces with the early house. He built the present house in circa 1820, retain-

ing the original house as an annexe to the left. In scale, this two-storey house has a modest five-bay façade with shallow bows either side

of a Doric portico and the windows set within blank arches. The family purchased many pieces from noted Dublin cabinetmakers which

represented personal preferences but also the aesthetic values that motivated the wider society in which they lived. The choice of furniture,

at Kilsharvan House, demonstrates a desire for conformity within their own social milieu and differs from the grand antique referenced

schemes of the very wealthy or those engaged in social advancement. These houses also epitomize the problems with studying the building

and furnishing of mid-sized Irish country houses, as few records are available.(iii) The house passed into the McDonnell family through

marriage, after Andrew Armstrong’s only son was killed at the battle of Fetrozan in India in 1845 and it remained in the possession of the

McDonnell family until sold in 1998. The contents were dispersed shortly after the house was sold, with the furniture sold at James Adam,

St Stephen’s Green, Dublin. These largely dated from the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Like many houses with modest facades,

the interior at Kilsharvan has fine detailing, with a gracious entrance top- lit hall, a fine sweeping staircase and ornate plasterwork. The

decorative quality of gilt wood stands in contrast with the taste for architectural mahogany pieces as (Lot 596), a fine corner cupboard with

a scrolled broken pediment ‘so loved by the Irish cabinet-maker’.(iv) This piece c 1760-1780 opens to reveal shaped shelves for display, with

the corner effect formed by a wonderfully constructed dome.

The Regency period with an increase in rents brought a flurry of country house building and furnishing. In the early nineteenth century the

dining room was the most splendidly furnished room by the early 1800s. By that period it had become a centre of male hospitality but by

the 1820s it had once again become an area for mixed-gender entertainment and family activity. Surviving bills and newspaper adver-

tisements confirm that, by the 1830s in Dublin, the dining room, with its ensemble of a large dining table, a set of dining chairs and other

storage and display furniture was an established ensemble for middle-class houses used for mixed-gender entertainment. Indeed, Mary

O’Connell invited guests for dinner even when Daniel O’Connell was away writing ‘You will say it is a bold thing for me to ask company in

your absence’.(v) The impression given from Robert Graham’s visit to Dublin in 1835 is that people entertained with style before attending