72

The Tain

Táin Bó Cuailnge

is the longest and most important of the Ulster cycle of heroic tales. In September 1969 The Dolmen Press published a unique

translation, largely from the eighth century Irish version, by Thomas Kinsella. (See lot 62A)

The Origin of the Tain

Much of early Irish literature has been lost. Much of what survives is contained in a few large manuscripts made in medieval times. Among their

miscellaneous contents are four groups of stories: mythological stories relating to the Tuatha Dé Danann (‘the Tribes of the Goddess Danann’), an

ancient divine race said to have inhabited Ireland before the coming of the Celts; the Ulster cycle, dealing with the exploits of King Conchobor

and the champions of the Red Branch, chief of whom is Cúchulainn, the Hound of Ulster; the Fenian cycle, stories of Finn mac Cumaill, his son

Oisín, and the other warriors of the Fiana; and a group of stories centred on various kings said to have reigned between the third century B.C. and

the eighth century A.D.

The oldest of these manuscripts -

Lebor Na hUidre,

familiarly known as the

Book of the Dun Cow

- was compiled in the monastery of Clonmacnoise

in the twelfth century. It contains, in a badly flawed and mutilated text, part of the earliest known form of the

Táin Bó Cuailnge

. Another partial

version of the same form of the story, also flawed, is contained in a late fourteenth century manuscript, the

Yellow Book of Lecan

. Between them these

give the main body of the

Táin

as used in chapters II to XIV of my translation.

The origins of the

Táin

are far more ancient than these manuscripts.The language of the earliest form of the story is dated to the eighth century, but

some of the verse passages may be two centuries older, and it is held by most Celtic scholars that the Ulster cycle, with the rest of early Irish litera-

ture, must have had a long oral existence before it received a literary shape and a few traces of Christian colour, at the hands of the monastic scribes.

As to the background of the

Táin

, the Ulster cycle was traditionally believed to refer to the time of Christ.This might seem to be supported by the

similarity between the barbaric world of the stories, uninfluenced by Greece or Rome, and the Le Téne Iron Age civilisation of Gaul and Britain.

The

Táin

and certain descriptions of Gaulish society by Classical authors have many details in common: in warfare alone, the individual weapons,

the boastfulness and courage of the warriors, the practices of cattle-raiding, chariot-fighting and beheading. Ireland, however, by its isolated position,

could retain traits and customs that had disappeared elsewhere centuries before, and it is possible that the kind of culture the

Táin

describes may

have lasted in Ireland up to the introduction of Christianity in the fifth century.

Thomas Kinsella,The Dolmen Press, 1969

56

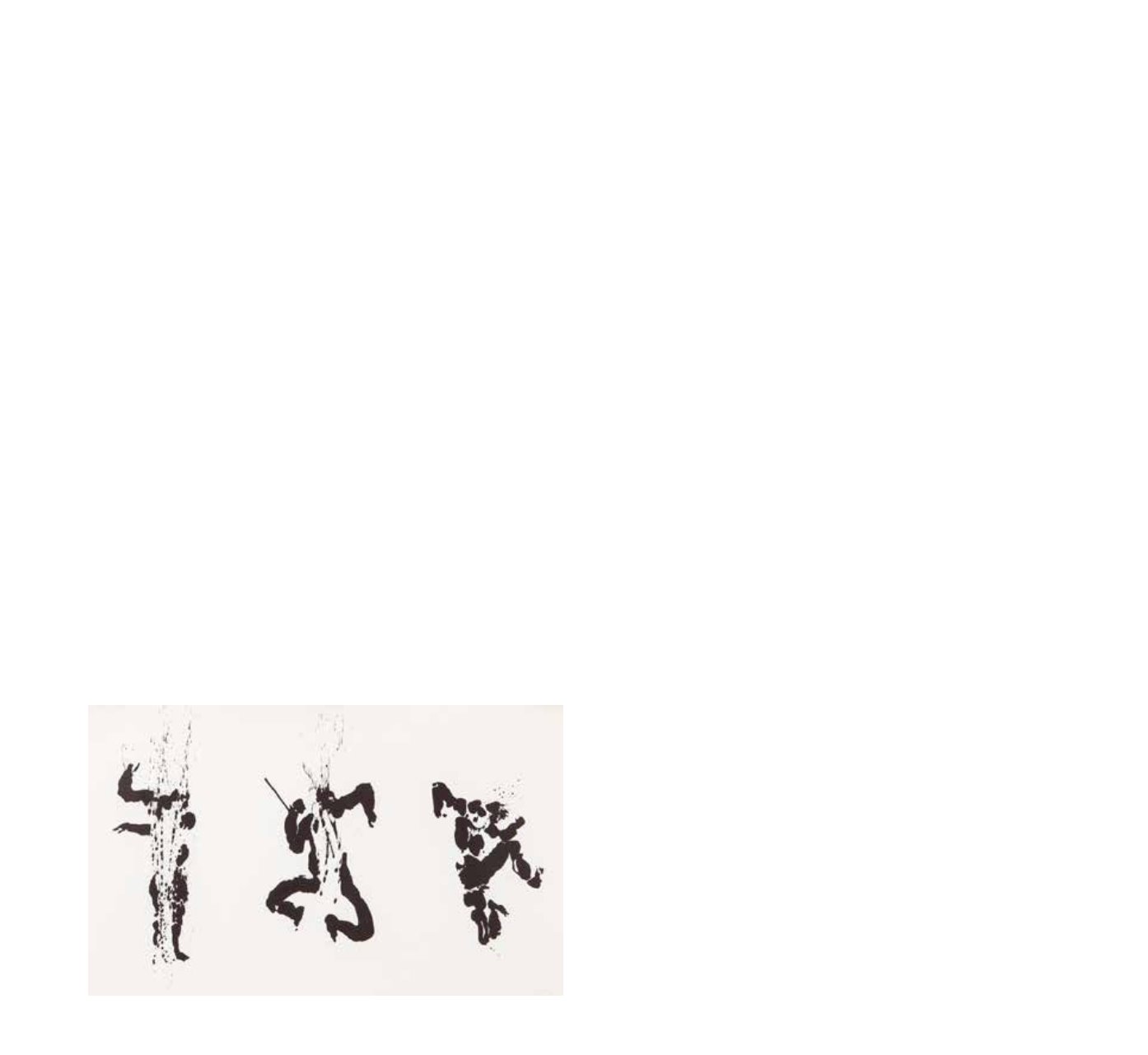

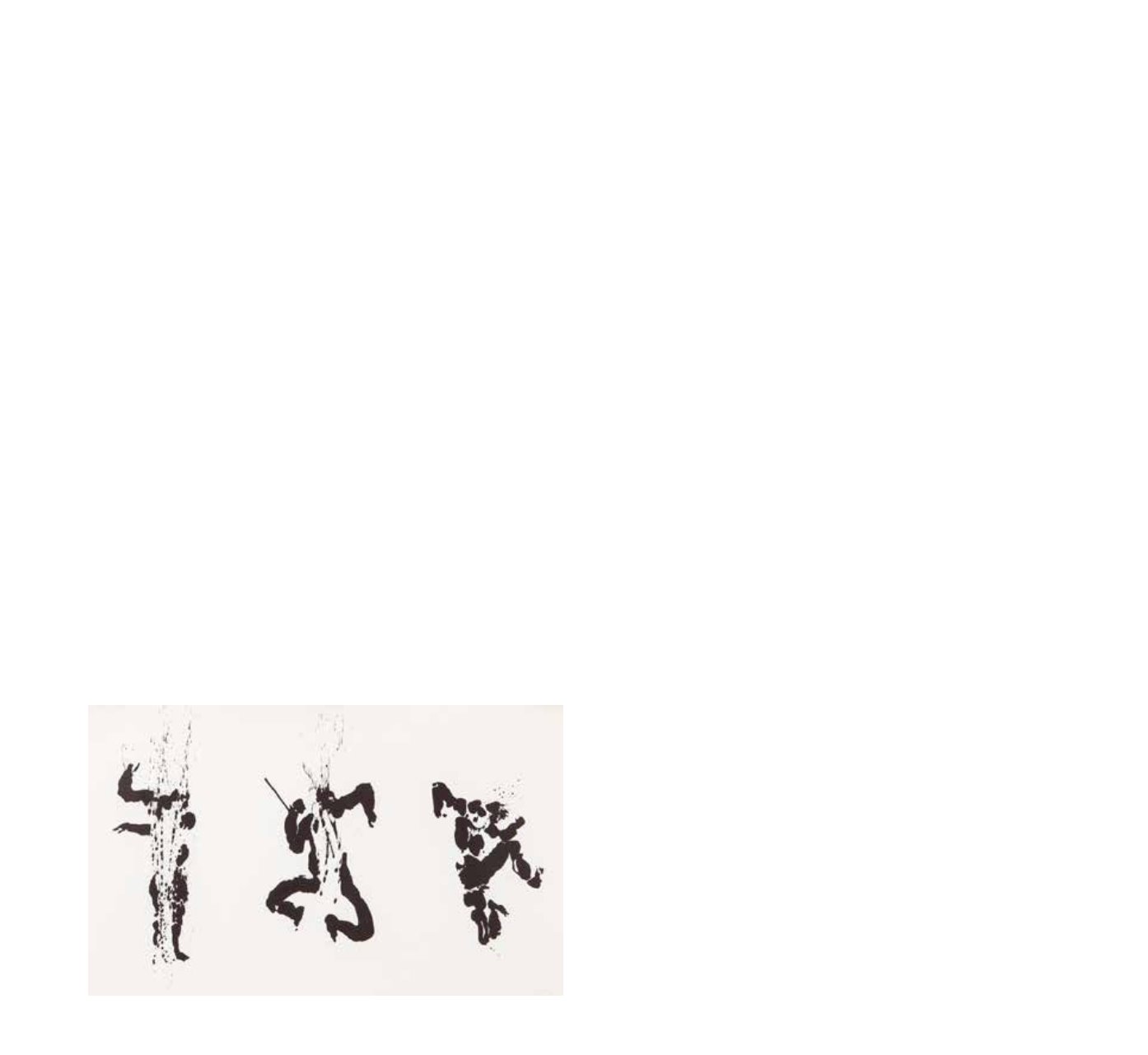

Louis le Brocquy HRHA (1916-2012)

Cúchulainn in Warp Spasm

Lithograph, 38 x 54cm (15 x 21”)

Signed, dated 1969 and numbered 6/70

Exhibited:

Louis le Brocquy: Lithographic Brush

Drawings fromThe Tain

Exhibition”,

The Dawson Gallery, Dublin, October 1969,

Cat. No. 41, where purchased by the current

owner

Illustrated:

The Tain,

Pages 151-3

€600 - 800

Lots 56 - 62 are the complete set of all ‘Tain’ Lithographs exhibited at the Dawson Gallery

1969